2 Jika iMfundo 2015–2017: Why, what and key learnings

Author and publication details

Mary Metcalfe, Director of Education Change, PILO, metcalfe.mary11@gmail.com

Published in: Christie, P. & Monyokolo, M. (Eds). (2018). Learning about sustainable change in education in South Africa: the Jika iMfundo campaign 2015-2017. Saide: Johannesburg.

Download PDFThis chapter intends to do two things:

- Provide the rationale and the key ideas informing this initiative for change-at-scale.

- Document in some detail the components of Jika iMfundo in order to frame the research pieces that follow and which interact critically with some of these key components. These sections include multiple examples of the detail of the interventions to give life to the abstract descriptions in the text and highlight key system learning from the work in 2015–2017.

The chapter does not report on the monitoring and evaluation of the intervention or the multiple ways in which learning from this trial-at-scale has informed subsequent re-design. The set of research reports in this volume and the external evaluation will be invaluable in informing that process. The tasks of reporting on monitoring and evaluation, and re-design for the 2018–2021 phase will be taken further in subsequent publications.

Brief overview of Jika iMfundo in Pinetown and King Cetshwayo, 2015–17

Jika iMfundo is a campaign of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education that has been piloted on scale in 2015–7 in all 1 200 public schools in two districts (King Cetshwayo and Pinetown) so that the model is tested on scale and lessons are learned before phased rollout across the province from 2018. The implementation of Jika iMfundo is supported by the Programme to Improve Learning Outcomes (PILO) and funded by the National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT). The interventions have been designed for implementation at scale with recurrent costing that can be accommodated within the department’s budget.

The management focus is on all Circuit Managers and Subject Advisers at district level and on all the School Management Teams at school level. The teacher focus is on providing curriculum support materials to teachers from Grades 1–12 (languages, maths and science). Jika iMfundo seeks to provide district officials, teachers and School Management Teams with the tools and training needed to have professional, supportive conversations about curriculum coverage based on evidence so that problems of curriculum coverage are identified and solved and learning outcomes improve across the system. It achieves this with a set of interventions at school and district levels. It works from foundation phase to the FET phase by building routines and patterns of support within and to schools that will have a long-term and sustained impact on learning outcomes.

The overarching strategic objective is to improve learning outcomes. The Theory of Change to achieve this objective is that, if the quality of curriculum coverage improves, then learning outcomes will improve. In order for curriculum coverage to improve, the following behaviours associated with curriculum coverage must improve: monitoring curriculum coverage, reporting this at the level where action can be taken and providing supportive responses to solve problems associated with curriculum coverage. These are the lead indicators that must change before we will get change in the lag indicators of curriculum coverage and then learning.

The goal is to make behaviours supportive of quality curriculum coverage routine (embedded and sustained) practices in the system. The tools and materials developed have been collaboratively developed with the intention of driving meaningful and substantive engagement around identifying problems and actively seeking the solutions together as well as providing support in relationships of reciprocal accountability.

Jika iMfundo: The programme to improve learning outcomes (PILO) model and change at scale

Jika iMfundo is an education intervention that has been run as a campaign between 2015 and 2017 in all 1 200 public primary and secondary schools in the two districts of King Cetshwayo and Pinetown in KwaZulu-Natal. The intervention has been designed and implemented by the Programme for Improving Learning Outcomes (PILO). Jika iMfundo aims to achieve improvements in learning outcomes across the system by simultaneously focusing on the capacity of different levels of the system – the school and the district – to monitor and respond to problems of curriculum coverage. The logic has been that, if more learners have the opportunity to learn by successfully covering more of the curriculum, the more overall learning outcomes will improve.

The Programme for Improving Learning Outcomes (PILO) is a change partner of the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education and other stakeholders in the Jika iMfundo campaign. The campaign has been supported by the National Education Collaboration Trust (NECT) since 2014. The support of government and the private sector through the NECT has been critical in enabling this pilot-at-scale.

PILO is a public benefit (non-profit) organisation with the long-term aim of developing methodologies for change at scale that will contribute to significant and sustainable improvement in the public education system. With support from a range of donors and after broad consultation and learning across the community of education practitioners between 2011 and 2013, PILO undertook a collaborative design process with both officials and teacher unions in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) from 2013. This resulted in the Jika iMfundo design framework (or model) being finalised and implementation began in all 1 200 schools in two KwaZulu-Natal districts from 2015.

Jika iMfundo is the name of a campaign designed on the principles of the PILO model. The campaign belongs to the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Education, the NECT and stakeholders subscribing to the campaign. It has been implemented over three years in King Cetshwayo and Pinetown with PILO as the change partner. The campaign will continue after the exit of PILO through the deepening of practices introduced in the campaign. Whenever Jika iMfundo is used in this chapter, it refers to the KZN site of learning for PILO and the various activities and interventions implemented as part of the campaign. Wherever PILO is used, it refers to design and re-design considerations which have informed the work of Jika iMfundo – but which considerations are being practiced and informed across other sites of intervention outside of KZN. Jika iMfundo is thus a term used to describe the set of interventions in KZN schools. PILO is used to describe core elements of the learning of PILO that informed the design of Jika iMfundo and continues across multiple provinces. Jika iMfundo is one application of the emerging PILO model as this is explored and refined through carefully monitoring and reflecting on experience on a district scale.

PILO will continue to be the change partner to the KZNDoE in the provincial rollout of Jika iMfundo which will take place across all 6 200 schools of the province between 2018 and 2021 in a phased process of implementation beginning with uMgungundlovu, uMkhanyakude, iLembe and uMzinyathi in 2018. This means that, in 2018, Jika iMfundo will be implemented in 3 150 schools in the province. A map of the province indicating the districts is shown below together with its national boundaries and international borders. All districts are contiguous with local government districts, but the metropolitan area of eThekwini is divided into two education districts, uMlazi and Pinetown.

The work of PILO is broader than its work in KwaZulu-Natal. PILO is also a change partner in other provinces.1 A similar application of the model was implemented in the “A re Tokafatseng Seemo sa Thuto” campaign in the John Taolo Gaetsewe District of the Northern Cape between 2015 and 2016 where PILO was the change partner of the Northern Cape Department of Education and the Sishen Iron Ore Company. Lessons learned have enhanced the model.

Each application of the PILO model provides an opportunity to learn from “the ground” and to refine the model for change at scale. PILO gathers monitoring information that assists in assessing if the interventions are being implemented as intended and to monitor changes in the behaviour of educators and officials in order to shape the interventions formatively. There are intensive processes of internal reflection and refinement of the model and its modalities of implementation across school and district contexts. Alignment is maintained in the change process by deepening understanding of challenges and adjusting design in response to reflection on these challenges and changes in practice across different contexts. In KwaZulu-Natal, there has been significant system learning that has required redesign. These learnings and the resultant refinements have provided proof of concept of the central design elements of the Jika iMfundo model: that systemic change requires support in tools, training and systemic reinforcement that are rooted, not in empty compliance, but in professional, supportive conversations that are evidence-based and which identify and solve problems.

The importance of the scale of the intervention cannot be over-emphasised. Change at scale is a pressing necessity in South Africa and has distinct methodological requirements. Change at scale is required because of the urgency of finding solutions that can achieve impact on scale in the South African context. Poor educational outcomes undermine sustainable development economically, socially and politically. Much of the investment that has been made by the CSI and donor sectors in many small or medium scale interventions has had limited systemic impact. Where changes have not been embedded in the routine practices of schools or district officials and where the change has not been adopted into the working culture and operations of the system at every level, these changes have not endured.

PILO’s conception of change at scale requires a methodology and design that fulfils at least ten necessary conditions.

Firstly, the change must be consistent with government policy priorities and assist in making the policy intentions of government routine in the work of officials and schools. All of the design elements of Jika iMfundo reinforce components of key government policy documents.2 In assisting government and its stakeholders to execute policy intentions, it was understood that,

improved teaching and learning [can] not be brought about by fiat, testing, or blaming but requires investing in the capacity of the system to do better (Levin, 2010, p. 27).

Much policy and bureaucratic fiat is characterised by magical thinking – the assumption that the pronouncement results in changes in schools without a plausible link of causation involving on-scale activities of support. In particular, given the pace and scale of system changes in South Africa, it is underestimated how much schools and districts have been subject to “a large number of initiatives, some of which seemed to them to be competing for their energy and attention” (Levin, 2010, p. 28).

The work of assisting in the execution of government’s policy intentions does provide evidence and deep learning about design and resourcing challenges within government policy that could inform policy and its implementation. These include: the ambitious scope and pace of CAPS and its perceived inflexibility; the tension between progression policy and the limits of the possibility of differentiation within the pace of CAPS; the challenging scope of supervision responsibilities of Heads of Department at school level relative to their teaching load; the impossible scale of supervision for Subject Advisers who are often responsible for teachers in many hundreds of schools; the non-alignment between the institutional structure of schools as primary and secondary and the Inter-Sen curriculum structure particularly as this translates into the neglect of the Senior Phase and the support of teachers responsible for Grades 8 and 9; and the pervasive shortage of textbooks – particularly in Grades 8 and 9 – and reading material and other resources. All of these policy and resource considerations undermine the achievement of government’s strategic goals.

Evidence of these challenges is being rigorously gathered for constructive policy engagements with government at provincial and national levels. Where the work of PILO produces insights that could inform the policy and implementation process, these are shared with government and other stakeholders in appropriate fora.

Secondly, responsibility for implementing the change must be located where the responsibility will remain for sustaining the programme. Jika iMfundo in King Cetshwayo and Pinetown has been and will continue to be a campaign owned by the districts themselves and by the schools for improvement within these schools. The second phase of Jika iMfundo in Pinetown and King Cetshwayo from 2018 will be driven and monitored by the two districts, supported by the provincial education department as part of the provincial rollout and supported by PILO at both provincial and district levels. The changes achieved so far will need to be further reinforced by the district and province. Schools and officials, which are struggling to adopt the new practices, will need further targeted support.

Thirdly, the programme of change must focus on the embedding of the new behaviours within the professional repertoire of the educators and officials. Policy intentions and instructions do not change behaviour. These are filtered through what educators and officials already understand and believe, what they are convinced will work in their context and what they think is possible. There is a core principle informing the PILO approach to embedding new behaviours: the PILO model is built on a positive appreciation of how educators and officials exercise agency in their daily choices. Compliance alone is insufficient as an engine of meaningful and enduring change. Passive compliance is alienating to professional agency and sense of responsibility. Change requires personal purpose and commitment. This principle is key to the design of interventions that remind participants of moral purpose, of their agency, of those contextual matters over which they have influence and can exercise mastery, and make a difference with a sense of urgency, while communicating a compelling vision of change consistently in leadership practice and action.3

Moral purpose is an important starting point. It has been invariably our experience that teachers are motivated by a desire to achieve learner success and wellbeing. However, moral purpose is not enough on its own.

Levin (2012) argues,

Real improvement is only possible if people are motivated, individually and collectively, to put in the effort needed to get results. Changed practice across many, many schools will only happen when teachers, Principals and support staff see the need and commit themselves to make the effort to improve their practice and when students and parents see that the desired changes will be good for them too (p. 13).

Levin emphasises “positive morale” which requires that people have “real involvement in the changes rather than being on the receiving end of order they don’t agree with or don’t know to carry out” (2010, p. 66). This principle was significant in informing design and practice. For example, at district level, officials themselves designed the shared tool that was developed to guide their interactions with SMT. At school level, the SMT and teachers were encouraged to take the tools offered and adapt them to their needs and to improve existing tools and practices.

Fourthly, personal agency, or purpose, is not enough to produce mastery. Personal commitment to a vision of a better practice has to be supported by tools, by training and by systems which support the adoption of these behaviours as routines that are core to the work of the district and school, and which are reinforced by the experience of success in how these make it easier for educators and officials to succeed in their work.

Fifthly, a broad alliance of key stakeholders is necessary to ignite and sustain change, especially in education. Influence is distributed within systems and the more different centres of influence maintain alignment to a shared purpose and urgency, the greater the contribution to success. This is true of provincial, district and school levels. A broad alliance committed to change stabilises the system and maintains momentum through its inevitable setbacks and disruptions.

Focus Group research conducted for PILO (Perold, 2012) showed that education stakeholders in KZN were ready for change. They were committed to teaching, regarded education as a critical success factor for South Africa and were extremely concerned about poor learner performance in their schools. Many were also frustrated and demoralised because they felt that they are unable to bring about change and felt burdened by compliance demands and lack of support (Perold, 2012). Maintaining alignment of purpose in the alliance of stakeholders within schools, within districts and between stakeholder groupings was sustained by this core commitment to learner performance and a vision of change that they could believe in.

Teacher unions, especially SADTU, were fundamental partners in the coalition for change in Jika iMfundo. Regular reporting and consultation meetings are convened with the teacher unions at provincial, regional and branch level. These meetings are invaluable as an opportunity to co-design and as a source of monitoring information which guides implementation. The SADTU 2017 conference adopted a resolution on the expansion of Jika iMfundo building on positive reports in conference and made an explicit commitment to ownership of the rollout. While engagement with SADTU was most regular because of the size of its membership in the province and the number of its structures, the other key unions were also consulted and kept informed. When the campaign was introduced to schools in a sign-up process, messages of support from the unions were shared and SADTU sent representatives to the venues.

Jika iMfundo is being run as a campaign to be joined by all role players. The by-line, “what I do matters”, represents the appeal to moral purpose and recognition of the agency and impact of professionals. Jika iMfundo was the integrating theme across all elements of the intervention which included: the Curriculum Planners and Trackers assisting teachers to plan teaching and assessment and to track curriculum coverage; the SMT training for HoDs, Principals and deputies; the content training for HoDs and subject and phase leaders at school level; and the work at district level. This gave coherence to the central messages of both “what I do matters” and the vision of focusing on improving curriculum coverage in order to improve learning outcomes. This goal was one to which all role players at different levels could relate in terms of an organising principle for their work. The reason that curriculum coverage was chosen as the focus is covered in the next section where the professional complexity of the concept is unpacked.

Sixth, monitoring and tracking must be integral to the change process within the school and the districts so that insights from evidence are used to respond to problems timeously and at the appropriate level. School management teams regularly track teachers’ curriculum coverage reports so that they can respond with the correct support. District teams gather and aggregate school level curriculum management data so that they can prioritise and respond to challenges at school level. The indicators monitoring the intervention were constructed to be systemic, not only for the life cycle of the intervention, but also for teachers, SMTs, the district and province to use for ongoing, systemic and routine monitoring and support. More than this, the improvements must be visible to the educators and officials. They must be able to track, validate – and celebrate – their own success because success motivates. Levin, in his 2010 seminal text on school improvement, concludes,

One of the fundamental lessons of research on human motivation is that people will do more of what they think they are good at, or can become good at (p. 235).

The change programme of Jika iMfundo uses tracking success as a motivator to “stay the course” and “accelerate the pace”.

In working at these macro and micro levels simultaneously, Jika iMfundo seeks to align the support-pressure balance within the school and between the school and the district. This is to propel technical “capacity building” constantly with the energy of human agency and the belief that, with the investment in effort, learners will have more chance of success.

Seventh, PILO’s approach to change is rooted in two conceptions of accountability: reciprocal accountability and internal accountability. Accountability is reciprocal rather than hierarchical and internal accountability precedes external accountability in well-functioning institutions. Both concepts of accountability are drawn from Elmore (2000, 2006, 2010) and are central to PILO’s approach to professional practice and agency.

Witten, Metcalfe and Makole (2017) describe PILO’s approach to accountability:

Central to PILO’s theory of change is the relationship between the different components and key actors in the system. A defining element of these relationships is the concept of accountability as proposed by Elmore (1999, 2006, 2010) … He suggests two types of accountability that are required for effective school improvement. The first is … ‘reciprocal accountability’ – which, in its simplest form, means that, for every unit of change performance that is required, an equivalent unit of support and capacity should be provided to those responsible for the change. … In PILO’s approach to its work, the essential question of ‘How can I help you?’ is central to its approach in improving curriculum coverage and the extent to which this professional disposition and approach permeates throughout the system will be instrumental in determining its success.

The second type of accountability that Elmore suggests is important for school improvement is that of ‘internal accountability’, which occurs within an organisational unit like the school or a team. Elmore argues that it is the ‘… degree of coherence in the organization around norms, values, expectations and processes for getting the work done …’ (Elmore, 2010, p. 6).

Schools are unlikely to be able to respond to external accountability without practices of internal accountability. City, Elmore, Fiarman and Teitel (2010, p. 37) argue that schools with “a chronically weak institutional culture … have no capacity to mount a coherent response to external pressure, because they have no common instructional culture to start with”. Jika iMfundo seeks to establish a common instructional culture of curriculum management of tracking, reflecting, reporting, monitoring and collaborative problem solving. The strong theme of professional judgement in all the components of the campaign is an internal and external professional accountability based on rigorous evidence with strong mechanisms of (reciprocal) accountability.

In “Schools that Work” (Christie, Butler, & Potterton, 2007), Christie draws on the work of McLaughlin (1987) who notes that

change to the smallest unit of the system – teachers and learners in classrooms – is hard to reach from the top, given the multiple layers of education systems. Change at the level of this smallest unit requires a strategic balance of pressure and support. Pressure alone seldom changes people’s beliefs (though it may be used to bring behavioural change). Support alone allows other priorities to take precedence. Change involves both people’s capacity and their will and while the former may be changed relatively easily (e.g. through good training or ‘capacity building’), the latter (involving beliefs and motivation) is far harder to shift. It would be a mistake to interpret McLaughlin’s point as behaviourist; what she is advocating, rather, is that change be viewed as a process of negotiation rather than imposition. In changing school practices, it is necessary to work with both the macro-logic of systemic level concerns and the micro-logic of schools, teachers and classroom.

Eighth, the primary site of teacher professional development in South Africa is inevitably the school. Teachers may, or may not, have regular opportunities to participate in professional development opportunities provided by their employer, by their union or by professional associations, in professional learning communities across schools or other activities that are self-driven. The further teachers work from where they live, the distances they need to travel and their personal resources all constrain how frequently these opportunities may be taken. Schools are the places where teachers interact with colleagues professionally on a daily basis and formally or informally share challenges and explore solutions. PILO has therefore sought to strengthen internal institutional practices that support the functioning of the school as a Professional Learning Community.

There is much in the education literature that supports this approach. OECD research has shown that the more teachers collaborate, the greater is their belief in their ability to teach, engage students and manage a classroom (OECD, 2016, p. 199). The 2016 TALIS report argues that Principals “have the means of improving teacher quality through actions such as fostering a professional learning community” and evidence is given for a strong association between teacher characteristics, specifically, teachers’ self-efficacy, with the implementation of professional learning communities (OECD, 2016). Mourshed, Chijioke and Barber (2010) found that, in improving systems, teachers and school leaders work together to embed routines that nurture instructional and leadership excellence in the teaching community, making classroom practice public and developing teachers into coaches of their peers (p. 21–22).

Timperley (2007) identifies seven elements “as important for promoting professional learning in ways that impacted positively and substantively on a range of student outcomes.” One of these is active school leadership in which leaders “actively organised a supportive environment to promote professional learning” (Timperley, Wilson, Barrar, & Fung, 2007, p. xxvii). City et al. (2010) argue that professional development must be “deliberately connected to tangible and immediate problems of practice to be effective.” City has also argued that “teachers learn in settings in which they actually work, observed and being observed by colleagues confronting similar problems of practice” (p. x). For a school to build practices that enable it to function as a professional learning community, internal accountability systems and practices must be characterised by a culture of professional, supportive, evidence-based conversations. Like City et al. (2010), Talbert and McLaughlin (1994) argue that “privacy norms characteristic of the profession undermine capacity for teacher learning and sustained professional commitment” (p. 124).

For Elmore, the organisation of the school and its practices of accountability must, by design, create processes of teacher improvement which take teachers out of the isolation of self-contained classrooms into collective learner – and learning – focused reflection that is normative and builds professional knowledge. Jika iMfundo seeks to promote professional learning communities at school level by creating the organisational arrangements and routines that promote collaboration and the de-privatisation of professional practice.

Jika iMfundo’s emphasis on teacher collaboration is supported in an analysis of highly performing schools in South Africa – the 2017 National Education Evaluation and Development Unit (NEEDU) report, Schools that Work II: Lessons from the ground. In the Jika iMfundo training and coaching, forms of teacher collaboration referred to in the report were explicitly taught and were focused on the identification and solving of curriculum coverage problems. At the level of the teacher and the teaching team, this focus is on identifying problems of pedagogy and their impact on coverage. At the level of the SMT, it is curriculum management to improve coverage.

Ninth, in order to be sustainable, the change must be systemic. If attempts are made to change an element of the system but that change is not reinforced systemically, the system will undermine the embedding of the desired change. Peurach (2011) argues:

The logic of systemic reform held that ambitious outcomes would not be realised with piecemeal, uncoordinated reforms. Rather, the problems to be solved were understood to be many and interdependent (p. 6).

Jika iMfundo was designed to be coherent and mutually reinforcing across the practices of district officials and schools. It was realised that the long-term sustainability of changes at schools would need to be sustained by the support of district officials, not countermanded. It is for this reason that Jika was implemented across all schools in a district and with the support of the province. All elements were co-designed with the responsible officials at provincial level and taken forward under their line-authority. This approach is being deepened in the 2018 phase of rollout with Jika iMfundo activities being led within the responsible provincial Chief Directorates and integrated into their annual performance plans.

Tenth, the design must be scrupulously costed to be replicable at scale within the resource constraints of government. A pilot for scale must be costed for replicability on an even greater scale. This is especially true for the human resource components of any model. In the case of Jika iMfundo, the interventions proposed initially had to be re-appraised and rigorously remodelled so that they were implementable within the resource constraints of the human resource provisions in the KZN districts and the supervision resource constraints within schools.

This design principle is critical to understanding and reviewing Jika iMfundo. The “dosage” of the intervention is extraordinarily light relative to many interventions. We would love to have done more to support the educators and SMT members, but the rule of thumb was that, if there were not the resources within the system to do this on scale, it could not be part of Jika iMfundo. The experience of so many excellent “pilot” interventions is that they are resource-intensive and not designed for scale and are therefore not, sadly, scalable.

Because of this discipline, it is now possible for the recurrent funding of the provincial rollout of Jika iMfundo across all 6 200 schools of the province between 2018 and 2020 to be met from the provincial budget,4 while the costs of the change-support interventions (short-term) will be met by the NECT. The NECT evaluation framework of the 2015–2017 Jika iMfundo interventions characterises the PILO model thus:

The [PILO] Model emphasises a low-intensity (in terms of cost per school), management-focused intervention across all schools in the district. This is a behavioural change model that encourages the empowerment of the agency and motivation of HoDs, Deputy Principals and Principals. The Whole District Model also does not import any additional human resources into the school and district education ecosystems, but rather aims to reconstruct how existing [education role players] go about their job to improve learner outcomes.

Lastly, to effect change across a system is ambitious in itself and the scope of change must be relentlessly focused and consistent with the key elements of the theory of change. There should be no more “elements of change” than can be told as the story of and motivation for change by participants at every level – teachers, School Management Team members and officials. If there are more elements of change than can be told as a simple, compelling story of change, this will mean that focus and coherence is dissipated. For Jika iMfundo, the simple story was, “we are improving learning outcomes by improving curriculum coverage.” This was a compelling narrative that bound the different role players at different levels of the system to a shared programme of action even within a complex system with complex challenges. This narrative has inspired the collective action of stakeholders in the provinces where PILO has historically worked or begun to work.5

This focus had to be sufficiently clear and consistent to be maintained over time whatever the urgent and intrusive system challenges nibbling at attention and energy. PILO’s early diagnostic and focus groups showed that officials and schools were weary of change initiatives that had been poorly implemented without real change; “quick fix” solutions with unrealistic time frames; being over-burdened with multiple instructions and few resources; plans being abandoned because of new and competing priorities; and of the multiple parallel and competing instructions filtering through the different silos in the education system.

Consistency and focus on a clearly understood and limited set of change objectives is key to stamina and focus. Most of all, underlying these objectives must be the principle that the official/educator must believe that the effort is worthwhile because the outcome will help them with the real challenges that they face in their work. Given these critical conditions for success and the building of confidence to sustain change, constant vigilance to change management processes is critical to the design and implementation of Jika iMfundo.

Curriculum coverage as the object of change in Jika iMfundo

The Jika iMfundo focus on curriculum coverage as the object of change must be understood across several dimensions and curriculum coverage itself must be understood as a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Each of these dimensions is central to the design of the CAPS Planners and Trackers, to the training of School Management Teams (SMTs) and to the work of district officials.

Firstly, curriculum coverage provides a lens for exploring the dynamics of the instructional core, which are learning-teaching-content, and that changes must take place if learning is to improve. Elmore (2008b) argues that the only way in which learning outcomes will improve is through improvement in “the complex and demanding work of teaching and learning” in the instructional core, by “influencing what teachers do and when they make the practices they are being asked to try work in their classrooms”. In his view, the influence that SMT members have on “the quality and effectiveness of classroom instruction is determined not by the leadership practices they manifest, but by the way those practices influence the knowledge and skill of teachers, the level of work in classrooms and the level of active learning by students” (Elmore, 2008b, p. 1). The focus on curriculum coverage – with a particular emphasis on evidence of learning and its supportive management by the SMT – gives the SMT a direct “line-of-sight” into the instructional core.

Secondly, curriculum coverage provides the disparate components of the system with a common “message” of what needs to change. Teachers, SMT members and district officials all understand the fundamental necessity of improving curriculum coverage if learning outcomes are to improve and they understand the contribution of the role they perform in achieving this goal. The shared project of achieving curriculum coverage to which each component of the system is invited to participate is understood as integral to their collective core commitment – improving learning. This is maintained as the core moral and professional focus, and motivation throughout the implementation of the project. How these become routine in the institutional practices of each set of role-players is covered elsewhere in this volume.

Thirdly, curriculum coverage provides a vehicle for a SMT and the teachers it supports to establish routine practices of monitoring, identifying and solving problems of coverage as a key step in a journey of professional conversations that will be generative of increased professional development through reflection and collaboration on the basis of the real pedagogical problems in the classroom. The routine and structured monitoring of curriculum coverage is a “way into” an examination of learning and, as a consequence, into the privatised space of teaching practice that is related to this learning. This approach recognises that the primary site of teachers’ professional growth is the school. The SMT training and coaching invests heavily in guiding the SMT to supervise supportively so that teachers are open to sharing their challenges and revealing their inadequacies.

Fourthly, curriculum coverage is quantifiable, despite the complexities of quantification (as will be discussed later). Quantitative dates, which can be aggregated (as well as deconstructed qualitatively), make system level diagnostics above the classroom possible at school and district levels. Aggregated data that are routinely and regularly monitored, with reporting to the level at which action can be taken, can be used to respond supportively to problems identified. The Jika iMfundo pilot has enabled learning about ways to create dashboards of coverage information that can be regularly monitored, reported to the level where action can influence change and that action can be taken in a regimen of reciprocal accountability. Hargreaves and Braun (2013) argue that accountability contributes to improvement when there is “collaborative involvement in data collection and analysis, collective responsibility for improvement and a consensus that the indicators and metrics involved … are accurate, meaningful, fair, broad and balanced.” This is as true within the school as within the greater system. Their view that, “when these conditions are absent, improvement efforts and outcomes-based accountability can work at cross-purposes, resulting in distraction from core purposes, gaming of the system and even outright corruption and cheating.” In this next section, we will show how this “gaming” operates in relation to measures of curriculum coverage at schools and district levels.

Fifthly, curriculum coverage is a collective project that is amenable to work on scale and improvement on scale within the existing capacity of the system. Design for system replicability is a central goal of the intervention. Whilst social and economic factors erode learning potential, material constraints hamper education delivery and teacher knowledge and skill undermine their ability to deliver the intended curriculum. The planning and monitoring of curriculum coverage is within the zone of the short-term potential capability of all schools that have the capacity and desire to absorb the intervention. Improving curriculum coverage is a professional matter for which School Management Teams of officials can assert their agency, no matter how challenging their circumstances. Indeed, the routines of internal accountability and a culture of professional development are a necessary basis for further professional learning within the school.

The sixth point is that curriculum coverage is an acknowledged problem, a central concern of government and a key policy goal of the DBE’s Action Plan 2019 (2015a) as Goal 18 specifies: “Ensure that learners cover all the topics and skills areas that they should cover within their current school year.”

The DBE indicator for this goal is:

The percentage of learners who cover everything in the curriculum for their current year on the basis of sample-based evaluations of records kept by teachers and evidence of practical exercises done by learners (DBE, 2014, p. 13).

In 2011, performance against this the indicator was 53% of learners nationally (DBE, 2014, p. 40). The national target for 2016 was that this should be 66%. Learning deficits are cumulative in character. The DBE Macro Indicator Report (2013a, p. 63) indicates:

Poor learning outcomes can be traced to differential ‘input indicators’ or characteristics of school and teacher practices. The report showed, in particular, that incomplete coverage of the curriculum and inadequate teacher subject knowledge are examples of the problematic ‘inputs’ to educational quality.

The findings of the 2011 DBE School Effectiveness Survey (DBE, 2013b) are instructive in terms of coverage trends across grades and subjects. Unfortunately, there is no more recent study from which to draw. No large-scale survey with verification of documentation has been undertaken since 2011. The table below shows curriculum coverage (defined as completing the minimum number of exercises per week, for Grades 8 and 9.

| Grade | Subject | % Completing Minimum Four Exercise Per Week | Average # Written Exercises Per Week | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KZN | National | KZN | National | ||

| 6 | Mathematics | 40 | 31 | 2.8 | 2.5 |

| Language | 13 | 7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | |

| 9 | Mathematics | 4 | 6 | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Language | 0 | 0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | |

Curriculum Coverage Survey Grades 6 and 9 mathematics and EFAL

Table 2.1 Curriculum Coverage Survey Grades 6 and 9 mathematics and EFAL

Extracted from DBE (2011a).

In summary, these results indicate that coverage should be a grave concern for both KwaZulu-Natal and the country as a whole. In KwaZulu-Natal,

- only 13% of Grade 6 learners had covered a minimum of four language exercises per week and the average number of written language exercises per learner per week was 1.8 (DBE, 2016, p. 71).

- 40% of Grade 6 learners had covered a minimum of four exercises per week and the average number of mathematics written exercises per learner per week was 2.8 (DBE, 2016, p. 75).

- for Grade 9, no learners covered a minimum of four language exercises per week. This result was consistent across all provinces. The average number of written language exercises per learner per week was 1.1 (DBE, 2016, p. 79).

- for mathematics, 4% of Grade 9 learners had covered a minimum of four exercises per week (the national score was 6%) and the average number of mathematics written exercises per learner per week was 1.7 (DBE, 2016, p. 83).

Several observations can be made. Firstly, the number of written exercises completed each week (as a measure of curriculum coverage) in 2011 was far below the specification of the official curriculum nationally and in the KZN province. Secondly, the achievement of the set target of exercises was abysmal in language in particular and declined in both subjects between Grades 6 and 9. Thirdly, verification of learner exercise books is possible for written work, but not in respect of oral work which is a critical component of language study.

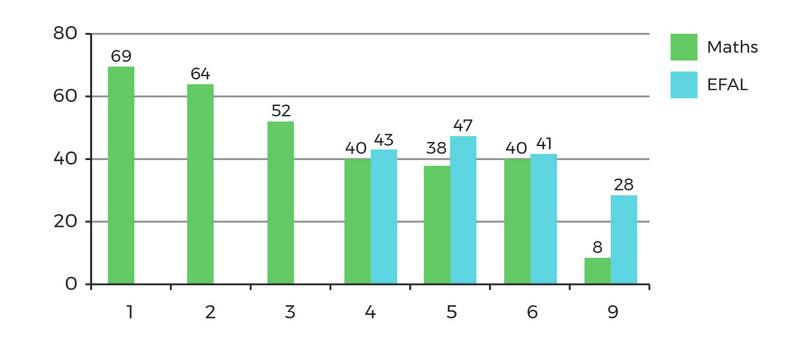

The Annual National Assessment (ANA) provides a proxy indicator for curriculum coverage. The construction of the ANA is “aligned to the coverage of work as indicated in the CAPS for the first three terms of the academic year” (DBE, 2014, p. 29). Figure 2.3 has been constructed from the 2014 ANA Report (DBE, 2014) to illustrate the ANA results comparatively across grades in mathematics and EFAL in 2014 in KwaZulu-Natal.

It is evident that the curriculum coverage deficit, in terms of the mastery of the official curriculum, is pronounced by the end of primary school. In the 2014 Annual National Assessment, in Grade 6, the average percentage mark in both mathematics and English First Additional Language (EFAL) (which is the medium of instruction in the majority of schools) was in the region of 40%. Such poor curriculum coverage, as measured by learner performance, is progressive and cumulative in both its causes and in its effects. This means that a teacher beginning the year with the Grade 7 mathematics class cannot assume that the concepts from previous years have been mastered. Learners in Grade 9 achieved only 8% and 28% for mathematics and EFAL in Grade 9. As learners proceed to Grade 10, they carry with them a massive deficit in the “opportunity to learn” that cripples their chances of success and makes the task of the teacher, in responding to the range of learning levels, overwhelming. The poor performance in EFAL negatively affects opportunities to learn in all subjects where this is the medium of instruction.

The DBE Action Plan 2019 (2015a) states that curriculum coverage is improving from its 2011 baseline of 53%:

This has occurred in the context of better guidance, through the Curriculum and Assessment Statement (CAPS) and national workbooks, on what work should have been covered by specific weeks of the year. The key challenge in the coming years will be to move from systemic research to practical tools that can be used by all districts and school Principals to monitor curriculum coverage. There is a real risk that must be managed, namely, the risk that monitoring leads to a ‘tick box approach’ to the curriculum, where teachers seem to comply with timeframes, but there is too much compromising in terms of depth and actual learning. In this regard, it has become increasingly clear that there is not enough good guidance offered to teachers on how to deal with a multitude of abilities within the same class. Decisions on when to move from one topic to the next in the curriculum, when some learners are still clearly struggling with the previous topic, are extremely difficult decisions for teachers. Support and guidance for teachers here is crucial (DBE, 2015a, p. 43).

It is precisely in the areas identified as challenges that PILO is working:

- [The development and testing on scale of] “practical tools that can be used by all districts and school Principals to monitor curriculum coverage”

- [Moving away from] “a ‘tick box approach’ to the curriculum, where teachers seem to comply with timeframes, but there is too much compromising in terms of depth and actual learning”

- [Developing system capacity and routines, on scale, for] “good guidance offered to teachers on how to deal with a multitude of abilities within the same class. Decisions on when to move from one topic to the next in the curriculum, when some learners are still clearly struggling with the previous topic, are extremely difficult decisions for teachers. Support and guidance for teachers here is crucial.”

The challenges of monitoring curriculum coverage problems, coverage compliance that compromises depth of learning and teacher support for solving coverage problems have been central to design of Jika iMfundo and to the learning from the intervention.6

Lastly, curriculum coverage was chosen as the object of change because of its manifest impact on “opportunity to learn”. The work of William Schmidt has shown that, while public schooling is seen as “the great equaliser” (Schmidt, 2010, p. 12), great inequalities exist in public education systems and that unequal educational outcomes are clearly related to unequal educational opportunities. He argues that “educational equality in the most basic, foundational way imaginable – [is] equal coverage of core academic content” (Schmidt, 2010, p. 12). He has shown that “whether a student is even exposed to a topic depends on where he or she lives” (2010, p. 13). He also shows that “socioeconomic status and opportunity to learn are both independently related to achievement” (2010, p. 16). This is of profound significance. Whilst Bernstein’s famous dictum that “education cannot compensate for society” may frame the challenges in which education works for social justice, opportunities to learn can compensate for socio-economic status. Schmidt defines “opportunity to learn” as curriculum coverage and concludes that,

the implication of our conceptual model is that by adopting focused, rigorous, coherent and common content-coverage frameworks, the United States could minimize the impact of socioeconomic status on content coverage (Schmidt, 2010, p. 16).

The Annual National Assessments can be seen as proxy for curriculum coverage, understood as mastery of the official curriculum. These results show a close correlation between coverage as performance and socio-economic quintiles. In the tables below, quintile one includes the poorest households and quintile five the most affluent. The achievement gap in mathematics at Grade 1 is 13%. By Grade 6, this has increased to 22%.

| Gr1 | Gr2 | Gr3 | Gr4 | Gr5 | Gr6 | Gr9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 | 65.1 | 59.2 | 52.5 | 32.8 | 32.1 | 38.1 | 10.1 |

| Quintile 2 | 66.6 | 60.2 | 52.9 | 34.3 | 33.4 | 39.6 | 8.7 |

| Quintile 3 | 67.4 | 60.4 | 53.9 | 35.6 | 34.5 | 40.4 | 8.2 |

| Quintile 4 | 71.2 | 63.5 | 58.0 | 40.4 | 41.2 | 46.1 | 9.2 |

| Quintile 5 | 78.4 | 71.4 | 68.9 | 52.9 | 55.0 | 60.3 | 21.6 |

Average % mark in mathematics by grade and poverty quintile, annual national assessment 2014 (DBE, 2014, p. 89)

Table 2.2 Average % mark in mathematics by grade and poverty quintile, annual national assessment 2014 (DBE, 2014, p. 89)

Jika iMfundo has trialled, on scale, the adoption of “focused, rigorous, coherent and common content-coverage frameworks” and tools and training to support focused system routines for identifying and seeking solutions to problems of coverage. As a system intervention, it has the potential to increase opportunities to learn across all quintiles, but some design elements focus on schools most needing support to overcome socio-economic challenges. For example, the subjects focused on include English First Additional Language (rather than First Language) as this automatically prioritises poorer communities as this coincides with race and class.

Jika iMfundo is but one contribution in the wide range of factors that constrain improvements in learning. The seminal Coleman study in the USA, Equality of Educational Opportunity (1966), found that personal and family characteristics had a greater influence on performance than characteristics of schools. While education inequalities are firmly rooted in societal inequalities and achievement is more closely tied to family background than to school resources, this does not mean that quality differentials in schooling do not matter. Coleman concluded that “it is for the most disadvantaged children that improvements in school quality will make the most difference in achievement” (1966, p. 22). The imperatives of both justice and efficiency require that what happens in schools and how schools are resourced must be interrogated to understand how schools’ practices might be changed to mediate greater success of the poor.

The Coleman report found that schools do make a difference for disadvantaged students, primarily through teacher quality, resources and curriculum (Christie, 2008, pp. 167–168): “A given investment in upgrading teacher quality will have the most effect on achievement in underprivileged areas” (Coleman, 1966, p. 317). Schmidt has similarly argued that opportunities to learn (by increasing curriculum coverage) can compensate for socio-economic status. This is the focus of the Jika iMfundo campaign.

Curriculum coverage: A complex and collaborative professional judgement based on assessment

What is “curriculum coverage”? As highlighted in the DBE Action Plan, it is not teachers “ticking” what they have taught as a compliance exercise. The understanding of curriculum coverage, as only reports of what is taught, is an inadequate descriptor of coverage. In this impoverished notion of curriculum coverage, coverage can improve – but at the expense of learning. Teachers’ reporting on what they have taught is a necessary and important component of the professional judgement of teachers of curriculum coverage, but it is only a first step towards the larger professional process of judging and reporting coverage as a function of what learners have learned as an indicator of curriculum coverage. Assessment practices – formal and informal – are at the heart of the monitoring of curriculum coverage and engagement with learners’ work as a practice is central to the professional practices and conversations introduced and deepened in Jika iMfundo.

Many monitoring surveys (including the Department of Basic Education’s 2011 School Monitoring Survey) focus on a partial definition of coverage – that of tasks completed and assessed, with physical checks of learner workbooks. This is a limited proxy for the measure of curriculum coverage without a parallel analysis of learning. For example, this approach might show a situation where none of the exercises for the last three weeks of a term had been attempted, but there may have been evidence of term 1 work having been done in term 2. Could this non-CAPS-compliance be the result of a considered and evidence-based professional judgement that key concepts in Term 1 needed more attention? Could this be an example of a teacher exercising agency and choosing a curriculum pacing that she considered to be in the best interests of her learners? This would be consistent with a study by Reeves and Muller (2005) referred to in the DBE Technical Report for the School Monitoring Survey (DBE, 2013b) which showed that,

… learners in Grade 5 and 6 are spending more time on subtopics that they were expected to have covered in earlier grades than they do on subtopics at the level expected for their grade. This shows evidence of slow curricular pacing across the grades and that learners are studying topics lower than grade level expectations (p. 57).

Other explanations are also possible:

- Could teaching-time have been lost in term 1 for a range of possible reasons? Is this a management problem creating coverage problems?

- Could the teacher be so concerned about the children performing poorly at the bottom end of a normal distribution curve that she was prepared to compromise the appropriate pace for children at the average to upper end of performance and did not have the necessary pedagogical skills of differentiated instruction to provide for this range?

- If the subject was English, could it be that the teacher’s professional judgement was that the level of fluency was so poor that she needed to spend more time developing oral fluency?

- In some subjects, such as mathematics, where teachers’ content knowledge is weak, could a similar pattern be an indication of teachers’ lack of confidence in the content that was not taught and the gaps be an avoidance mechanism?

What are the considerations that a teacher must manage in assessing coverage and how does a teacher make these judgements in her professional interaction with the guidance given by CAPS? The teacher interacts with the expected pace of progression of teaching of the content specified by CAPS by making judgements of what learners have learned. In making judgements and decisions regarding the pace of teaching in order to meet expectations of curriculum coverage in the specified time-frame, the teacher is influenced by her judgements of how many learners are performing at what level of achievement as specified in CAPS and at what levels of cognitive complexity. Teachers know that there will be a range of achievement from “not achieved” to “outstanding achievement” in a class – particularly given the wide range of difference in mastery of prior knowledge, given current progression policy and generally large classes. If the majority of learners in a class are achieving at a level below “adequate”, the teacher will need to make a judgement that, even if the time allocated for that concept is exhausted, the coverage problem will need to be solved. Her professional judgement will need to take into account:

- The cyclical nature of CAPS and opportunities that exist later in the year to revisit the concepts.

- How available time can be adjusted to allow for more time to consolidate the concepts relative to the weighting of the concept in CAPS and this judgement will be made relative to how much time has elapsed and how much time remains.

- How the relative importance of the concept in the foundational progression of the concept informs the prioritisation of that content relative to the work that still needs to be completed and, in some cases, this consideration of the relative prioritisation of the concept/skill means that it can be omitted.

Many considerations inform the judgements teachers are making but these judgements are too often made in privacy and not shared. A compliance-driven approach makes these judgements invisible and the “gaming” strategies that teachers are forced to employ include:

- Testing what they have taught rather than the full set of concepts and skills that CAPS requires.

- Testing at a cognitive level below CAPS expectations but at which the learners can succeed.

Teachers consistently report that they construct assessments on the basis of what they have taught, not what they should have taught. Indeed, this is consistent with the pedagogical compact of trust between learner and teacher. The work of teachers in relation to assessment, as an essential element of monitoring curriculum coverage, includes:

- how to prioritise “coverage” relative to the time available and the learners’ level of performance

- deciding what will be assessed

- deciding the cognitive level of the informal assessment task

- deciding how to “pitch” the content and the level of assessment relative to their expectations of the performance of the class. It is not likely that teachers will set an assessment task that they know the majority of their class will not achieve. It is for this reason that routine provincial or district “common tests” are both a cause of teacher resentment, but also may not reflect learner performance rather than what teachers have taught. Learners proceeding at a pace that is less than expected may “pass” the components of the test actually taught, but “fail” the common assessment because it includes new content.

These are collective, not individual, judgements because such decisions will have an impact on teaching in subsequent grades.

It is especially important to deepen understanding of the expectation of CAPS in relation to cognitive levels. In Fleisch’s (2007) summary of the research on pedagogy and achievement, he concludes that teachers who teach poorer schoolchildren tend to have lower expectations of what learners can achieve and tend to interpret the official curriculum to support their lower expectations and that children collectively achieve to the low expectations of their teachers.

Teacher judgements are invisible when they are not made in contexts of professional collaboration because of a compliance mind-set that insists that the curriculum must be declared to be covered at all costs. Teacher judgements and troubling problems can only be tested and resolved in a professional and supportive conversation in which the teacher feels “safe” to reveal professional decisions usually made in “private”. That is the purpose of the professional supportive conversation with the teacher and making it public in the immediate professional community must be the starting point for exploring the collective solution to the problem of curriculum coverage.

The concept of professional interaction with CAPS rather than compliance with CAPS is a discomfiting thought for many educators driven by a compliance mind set. The compliance requirement results in compliance reporting of what officials wish to hear rather than what is the reality of the classroom. Jika iMfundo invests substantially in making incomplete coverage visible as the first step in identifying curriculum coverage problems and in supportive professional interactions as the necessary condition to solving these.

The professional judgement of individual teachers is best exercised in the community of teachers whose work is affected by that decision. Teachers are members of a professional community whose collective work of achieving curriculum coverage affects other teachers. Where a teacher in one year is unable to complete the teaching of all concepts and skills necessary for a teacher in subsequent years to achieve curriculum coverage (because incomplete coverage has cumulative effects over time), decisions about solutions to curriculum coverage problems cannot be taken by individual teachers without reference to teaching teams.

The management of assessment and the use of assessment information to inform decisions regarding curriculum coverage is central to the Jika iMfundo programme. The SMT, as a whole, has a responsibility to monitor what was taught, what was assessed and what percentage of learners performed at a level that is adequate. The SMT has a responsibility not only to monitor “coverage” in this way, but also to support the Heads of Department (HoDs) in their leadership of solving curriculum coverage problems. Monitoring only that assessment has been “done” is a poor curriculum management practice. A SMT needs to assess the content of the assessment relative to the demands of CAPS. Where coverage has not been achieved, the SMT should know this before assessment is conducted. SMTs need to monitor that the assessment is at the cognitive level required for progression to subsequent CAPS content. The SMT needs to be able to monitor both if assessment has been set on the required content and also the level of difficulty (including) cognitive demand. This monitoring and the professional, evidence-based and supportive conversations that are part of the monitoring, identify problems in order to provide support in the resolution of these problems.

These practices of planning, monitoring and responding to assessment are an integral part of the Jika iMfundo CAPS planners and trackers given to all teachers each term and to the SMT training. These skills and practices are built incrementally over the three years. The work that is done at district level with Circuit Managers and Subject Advisers similarly builds the skills and attitudes required for professional, supportive conversations about curriculum coverage that are based on the evidence of both what teachers report of their teaching and assessment as a window into learning.

Curriculum coverage improvement that results in the improvement of learning outcomes must be the outcome of professional development processes that impact positively on teacher practices and the exercise of professional judgement in the instructional core. Supportive accountability mechanisms within the school that routinely support change in these practices are one way of building professional agency to improve curriculum coverage – understood as improving the quality and depth of learning while extending coverage of the scope of the intended curriculum. Teacher capability is strengthened by an institutional culture and practice that collaboratively monitors, supports and solves problems of curriculum coverage. The work of PILO in the Jika iMfundo programme and the development of monitoring tools used routinely in the school and the district to identify problems for the explicit purpose of assisting teachers to solve these problems can be a valuable contribution to the DBE’s desire to have “a workable methodology for tracking curriculum coverage in any class in a school” (DBE, 2015b, p. 44).

Having a workable methodology for tracking curriculum coverage in a school must be a central task of improving the system – and this methodology must be a core practice of teachers, the SMT and officials who support them. If the reporting of any indicator is going to be useful to educators, it must assist them to solve the problems they face and add value to their daily work of improving learning. It will not help to improve learning if it only adds another layer of burdensome compliance reporting – but with no support consequential to this reporting. The monitoring of coverage, as defined by learners learning, is a key indicator of the outcome of processes in the instructional core and must enable the core function of the SMT to support teachers to solve pedagogical problems associated with poor coverage. The role of the SMT and district staff is to receive and verify reports for the purpose of providing meaningful support. If such routines are systemic, the monitoring and evaluation of Goal 18 of the DBE Action plan will provide for regular system knowledge and responsiveness as envisaged by the DBE’s Action Plan 2019 (2015a). The Trackers used by the teachers provide exemplars of assessment with cognitive level each term and the SMT training guides the HoDs to review coverage by discussing examples of learners’ work.

The practices implied in the overview of curriculum coverage above are what drive the design of the Jika iMfundo resources, tools, training and coaching. The theory of change posits that, when these practices are in place, curriculum coverage will improve because problems in coverage are “de-privatised” and brought into an institutionalised space of collective reflection and collegial support.

A note on curriculum coverage, progression policy and the complexity of classrooms

Professional judgements about coverage are made in the context of a progression policy which allows for learners to repeat only one grade per phase. This results in learners being “progressed” without having achieved at the necessary level to master the concepts in that year. The DBE (2011b) National Policy Pertaining to the Programme and Promotion Requirements of The National Curriculum Statement defines progression as

… the advancement of a learner from one grade to the next, excluding Grade R, in spite of the learner not having complied with all the promotion requirements provided that the underperformance of the learner in the previous grade is addressed in the grade to which the learner has been promoted (p. x).

The rationale for the progression policy as provided in the DoE Guidelines for Inclusive Learning programmes (2005) is:

The developmental needs of learners should not prevent them from progressing with their age cohort as the value of peer interaction is essential for social development, self-esteem, etc. The 1998 policy on Assessment allows for learners to spend a maximum of one extra year per phase. An additional year over and above what the policy currently states may be granted by the head of education of the province. This would mean that learners experiencing barriers to learning may be older than their peers (p. 19).

This progression policy depends on the capability of the system to support “progressed” learners. For Grades 4–6, the DBE (2011b) National Policy Pertaining to The Programme and Promotion Requirements of The National Curriculum Statement document states,

A learner who is not ready to perform at the expected level and who has been retained in the first phase for four (4) years or more and who is likely to be retained again in the second phase for four (4) years or more, should receive the necessary support.

When learning barriers are identified in the classroom, the CAPS documents refer teachers to support structures at school and district level and the DoE Guidelines for Inclusive Learning Programmes (2005). For example, the CAPS maths Grades 4–6 indicate that,

[t]he key to managing inclusivity is ensuring that barriers are identified and addressed by all the relevant support structures within the school community, including teachers, District-Based Support Teams, Institutional-Level Support Teams, parents and Special Schools as Resource Centres. To address barriers in the classroom, teachers should use various curriculum differentiation strategies such as those included in the Department of Basic Education’s Guidelines for Inclusive Teaching and Learning (2010).

A teacher seeking assistance would find limited advice in the DoE Guidelines for Inclusive Learning Programmes (2005).

The consequence of the progression policy means that, in terms of learners’ needs, many classes are, in fact, multi-grade in terms of learner performance while teachers are required to adhere to the CAPS content for one specific grade. They are asked to achieve this through lesson plans and teaching while providing for differentiated learning and scaffolding assessment activities. This is a huge demand of teachers when the ANA results for KZN in 2014 indicate that, in Grade 4, only 40% of learners in maths and 43% in EFAL are mastering the required content and that these figures remain more or less constant from Grades 4 to 6. This suggests that the 60% who are not mastering the content must be progressed and the teaching and assessment must be CAPS compliant. In the context of the reality of the multi-level performance of learners in one class, this requires the exercise of professional judgement and collegial collaboration in interacting with CAPS.

The design of the set of Jika iMfundo interventions

The overarching strategic objective of Jika iMfundo is to improve learning outcomes. The theory – or logic – of change to achieve this objective is that, if the curriculum coverage improves (using a complex notion of coverage as not what teachers say they have taught, but what learners have learned at the required level), then learning outcomes will improve.

The monitoring and evaluation framework for Jika iMfundo was developed in 2013 with the support of the Zenex Foundation. The first phase examined the conceptualisation and design of the proposed programme and assisted in focusing and developing “whether programme goals and objectives were well formulated, whether programme activities and outputs were clearly specified and whether expected outcomes and associated indicators were specified” (Mouton, 2014). This clarificatory process preceded final programme design, the process evaluation process and monitoring, and outcome evaluation and impact assessment. This laid the basis for subsequent stages of process evaluation – “assessing if implementation and delivery of programmes were as scheduled … If programme activities were implemented properly and how are these received and experienced by the target group” (Mouton, 2014).

The monitoring and evaluation process led to a logic model where the outcome and impact evaluation was based on the premise that, in order for curriculum coverage to improve, the following behaviours associated with curriculum coverage must improve: monitoring of curriculum coverage (not of what teachers have taught, but of what learners have learned); the reporting of this at the level where action can be taken; and the provision of supportive responses to solve problems associated with curriculum coverage. These are the behaviours (monitored as lead indicators) that must change in order to achieve an improvement in curriculum coverage (the lag indicator) and, from that, to realise an improvement in learning outcomes. The theory of change underpinning the Jika iMfundo monitoring and evaluation framework posits that the change in the lead indicators (changes in curriculum coverage management practice) is a necessary precursor to the improvement in curriculum coverage that follows (or lags).

This chapter will not provide a comprehensive overview of the monitoring and evaluation framework or process. These elements of the framework are introduced here to explain the framing of the lead indicators regarding the practices of teachers, HoDs, Principals and district officials in the theory of change underlying Jika iMfundo. The logic of cause (intervention) and effect (programme outcomes or benefits) in the monitoring and evaluation framework of the programme are that, in order to improve curriculum coverage, necessary (but not sufficient) conditions are:

- Teachers are to consistently plan, track and report on curriculum coverage and reflect on teaching and learning

- Heads of Department are to regularly check teachers’ curriculum tracking and learners’ work, work with teachers to improve coverage and assist teachers with problems in relation to the curriculum coverage

- Principals (and Deputies) are to meet HoDs regularly to review the quality of coverage and tracking; take action to improve coverage; and supervise the overall management of curriculum in the school

- Circuit Managers are to engage with schools to identify and solve key problems around the management of curriculum coverage

- Subject Advisers are to train and support HoDs to supervise and support teachers in curriculum coverage

- District officials are to work across silos to ensure data-driven problem solving and support to schools.

Without achieving the systemic adoption of these key practices, it is unlikely that curriculum coverage (defined as learners’ demonstration of learning) will improve and without improved curriculum coverage, or “opportunity to learn” (Schmidt, 2010), it is unlikely that systemic measures of learning outcomes will improve.

In the monitoring and evaluation framework, these key practices are lead indicators for the lag indicator of improved curriculum coverage. Curriculum coverage, as a lag indicator of that behaviour change, if successful, becomes a lead indicator for the final lag indicator and the goal of the intervention – improvements in learner outcomes. This is shown diagrammatically in Figure 2.4.

|

Teachers

Consistently:

|

HoDs

|

Principals

|

Circuit Managers

Engage with schools to identify and solve key problems around the management of the curriculum coverage |

Subject Advisers

Train and support HoDs to supervise and support teachers in the curriculum coverage |

| ↓ | ||||

|

District officials

Work across silos to ensure data driven problem solving and support to schools |

||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Curriculum coverage improves | ||||

| ↓ | ||||

| Learning outcomes improve | ||||

The Jika IMfundo Theory of Change for monitoring and evaluation

Figure 2.4 The Jika IMfundo Theory of Change for monitoring and evaluation

The achievement of each of these elements of the causal sequence (behaviour change, improvement in curriculum coverage and improvement in learning outcomes) is not simultaneous, but is sequential with an assumption of causal sequence. The consolidation of each lead indicator leads to improvement in its lag indicators and the impacts of each should have a cumulatively positive effect over time. The more curriculum coverage improves from one year to the next, the more likely it will be that the learner will be able to cover the curriculum in subsequent years. The monitoring and evaluation of these indicators to measure progress in 2015 to 2017 will only be of initial improvement. On-going consolidation of these changes, if sustained, will progressively, over subsequent years, result in even greater improvement.

These are necessary, but certainly not sufficient, conditions for improving both curriculum coverage and learning outcomes. So many extraneous factors (or “validity threats” in Mouton’s language) can negatively or positively impact either of these “lag” indicators. But, what is certain is that these practices and the collaborative culture and climate that must support them are certainly necessary conditions to lay the institutional basis for improving curriculum coverage.

In the face of these daunting structural challenges, the approach taken in designing the Jika iMfundo intervention was to focus on what could be changed, within human agency, in the short-term and on-scale. Teachers continue to teach despite the material constraints and despite the real impact of poverty on the learning-readiness of the children that they teach. They continue to do so without substantive opportunities to improve their content or pedagogical knowledge on-scale. The design of the intervention was premised on providing:

- teachers with support to navigate planning for teaching and assessment with minimal resources

- instructional leaders at school level (heads of department and subject or grade leaders) with opportunities for considering key conceptual challenges in that phase and subject at the start of each term (the “Just-in-Time” training)

- instructional management leaders (Heads of Departments and Principals and their deputies) with both the professional understanding of CAPS and its assessment in order to lead the management of the curriculum, as well as the adaptive and technical tools to put in place routine behaviours of curriculum management.

In making these design choices to achieve change at scale, we are aware that these modest interventions cannot compensate for the overwhelming contextual disadvantages. We have therefore not set ambitious goals for improvements in learning outcomes. We do however believe that improvements in the supportive management of curriculum and its coverage will result in modest improvements in learning relative to schools where such practices are absent and that they will lay the institutional basis for ongoing improvement.

The behaviours – or as PILO names them, key practices – described in these lead indicators are surprisingly modest because they are fundamental cogs of practice generally assumed to be in place in schools and districts but without which aspirational education improvement instructions and goals are hollow. Relative to the torrent of instructions that pour onto the desks of school and district leaders, these may seem trivial and are certainly taken for granted. We would argue that, in choosing these practices for this massive investment, we have chosen “those changes that have the most potential for the most students with the least effort” (Levin, 2010, p. 68).

Whilst it may be true that, relative to many of the other ambitious policy dicta, the achievement of these practices should be a simple matter, we have found that this goal is deceptively ambitious, firstly, because of ingrained ways of behaving that are resistant to change despite a will to do so and because considerable system and individual capacity building is necessary. Levin (2010) concludes that,

… where performance is weak, so is people’s knowledge or skill as to how to do better. Improving system performance requires a large and sustained effort to improve skills (p. 234).